Japanese Black Wagyu Breed Development Strategies

This section looks at the modern state of the Japanese Black Wagyu herd, now challenged by diminishing genetic diversity caused exclusively by intensive selection for a single (meat quality) trait. We skim the Japanese animal science that identifies this challenge to the once proudly unique tsuru of the traditional Chugoku district, and the parallel commoditization and march to uniformity also confronting Japanese Black genetics elsewhere.

Nonetheless, Japanese studies involving prefectural calf market and carcass comparisons have demonstrated significant performance differences between some prefectural herds well into the 21st century. Japanese animal science has called for genetic preservation programs and detailed schemes to modify the selection practices which some see as bringing the breed to a crisis. Illustrative tables are reproduced below.

After reviewing the post-1980s swing to Hyogo (Tajima) bloodlines in the national herd which was the catalyst to challenged genetic diversity, we identify a sire-level swing back to larger Tottori (Kedaka) sire genetics by 2010. Evidence for this can be examined cursory pedigree analysis of prefectural bloodlines within the leading contemporary sires of Japan, which are detailed in the ‘Sire Rankings’ for Japan on this site.

Similarly, more detail on the individual the five key prefectural herds of Chugoku is available in the ‘Key Bloodlines’ subsection.

Modern Bloodline Performance Differentiation

How much have the domestic Japanese Black Wagyu herds of today lost prefectural differentiation and become genetically homogenous, with performance consistency?

Although the identification of a threatening genetic convergence towards a homogenous, inbred Japanese herd has fueled a prominent thread in Japanese Black Wagyu scientific discussion since the 1990s, Japanese science of the early 21st century has also presented evidence that economically important genetic differences remain between the remnant sub-populations of the five historic Chugoku ‘Black Wagyu cradle’ prefectures of southern Honshu – probably most significantly in female populations.

According to scientific literature published as recently as 2002, modern Chugoku ‘cradle’ prefectures continue to support unique tsuru cows and differentiated genetics with substantially varying performance characteristics. These prefectural characteristics are deemed sufficiently important to rate everyday mention in major Japanese sire catalogues, with comments such as “Good with Fujiyoshi female” being commonplace.

Prefectural genetic origins (those of genetic founder animals) identified in pedigrees are therefore important in everyday selection in Japan – perhaps not as important as progeny test results or EBVs based on carcass results, but an important part of the mix nonetheless.

There is no reason whatsoever why founding genetics data should be less important in non-Japanese, global Japanese Black herds, given the fact that Australian and American pedigrees retain this prefectural origin data and also given that most exports took place in and around the time frames of the studies referenced in this review.

In fact, given the lack of any comprehensive selection tools based on hard carcass data, the combination of pedigree analysis with phenotype review is the logical starting point for any analysis of a fullblood Japanese Black animal in Australia or the United States.

Comparative Calf Performance Analysis

Hyogo (Tajima) vs Tottori Prefectures

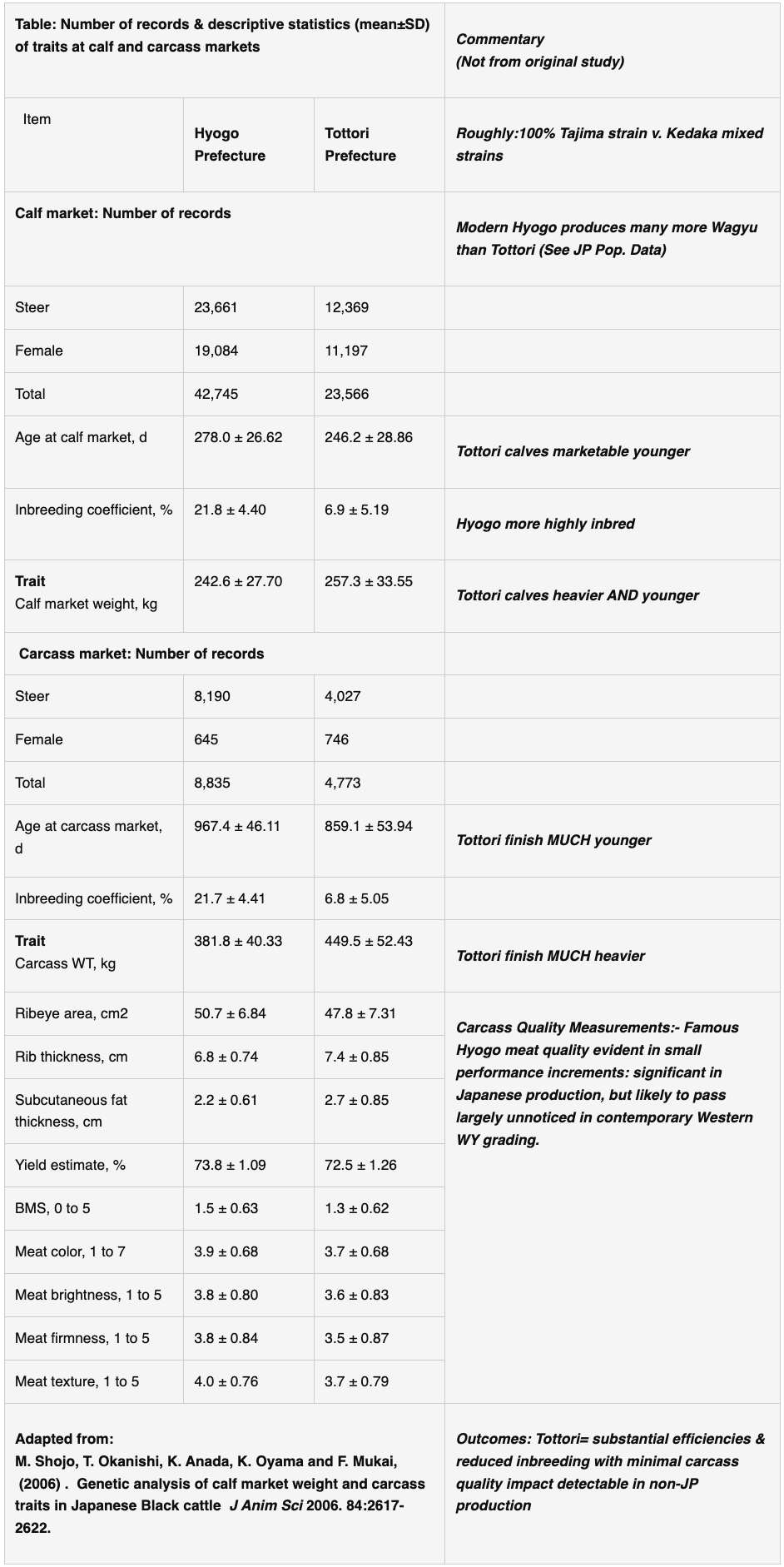

Potent evidence of performance differentiation by prefectural origin is in the calf analysis below. Authored by leading Japanese animal scientists using official data, this compares 1994-2002 drop progeny from two dominant ‘cradle prefecture’ herds. First published in a highly prestigious US animal science journal in 2006, the table summarises foundation data for a comparative study of genetic influences on market weight and carcass performance. (Added commentary at right is strictly for the dozing analyst).

Number of records & descriptive statistics (mean±SD) of traits at calf and carcass markets

(Click for larger picture).

The entire paper was available free and on-line in the Journal of Animal Science. A long series of academic studies of pedigree and prefectural genetic differentiation within the Japanese Black took place in Japan from the mid-1980s until about 2007. Clear genetic differences between Hyogo, Shimane and (to a lesser extent) Tottori cattle were further confirmed in a Texas A&M study around 2001. Genetic/performance differentiation between the individuals of specific prefectural herds is beyond doubt.

Modern Prefectures Maintain Unique Tsuru Genetics

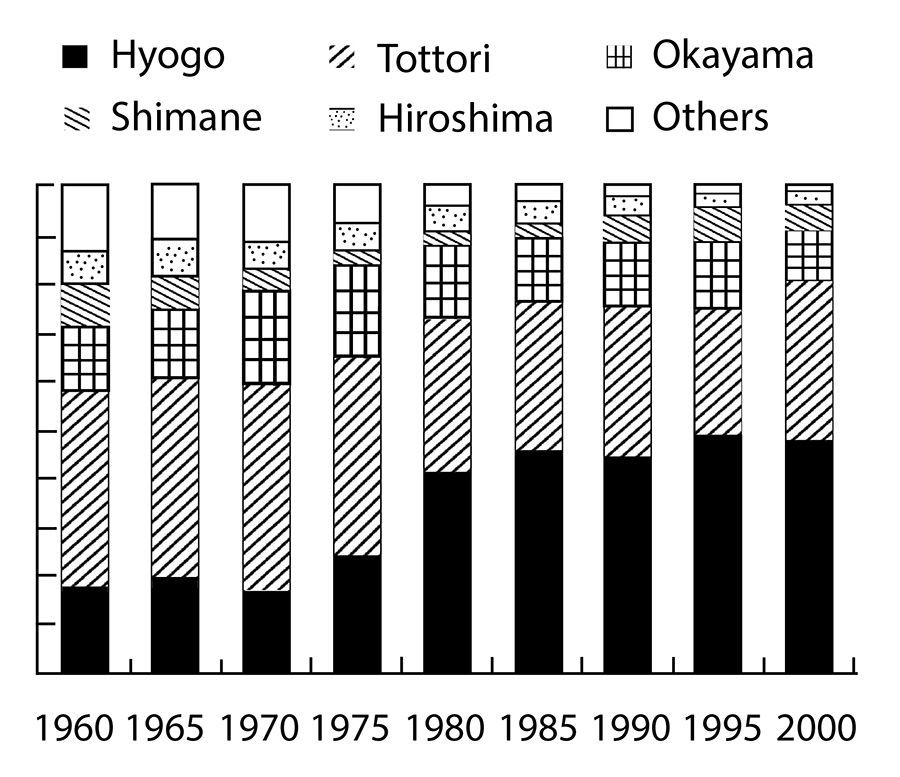

Another thing that is indisputable in Japanese Black breed development since the 1960s is the overwhelming impact of a ‘Tajima’ trend, which accelerates sharply after 1991. The following, simplified chart from Honda et al (2004) reveals the contribution of founders summed up by birth prefecture, and illustrates the impact of Hyogo (Tajima) genetics since 1980.

While Hyogo is the only prefectural herd closed to genetic imports, by 2000 the exported Hyogo genetic contribution to the national herd increased to 40%. As indicated, Tottori contributions dominated earlier, and would possibly feature prominently in any returned emphasis to overall carcass efficiency.

Adapted from Honda, T., Nomura, T., Yamguchi, Y., & Mukai, F. 2004. ‘’Monitoring of genetic diversity in the JP Black WY population by the use of pedigree Information’, J. Anim Breed. Genet. Berlin

(Click for larger picture)

The well-documented downside of this single-minded pursuit of a particular meat quality is the previously mentioned increased inbreeding and potentially permanent loss of genetic diversity.

The Hyogo/Tajima trend may now have slowed. Although there were no new herd pedigree analysis studies identified by 2012, analysis of top Japanese sire bloodlines as early as 2007 showed a resurgent emphasis on the production efficiencies of the larger Kedaka and Itozakura genetics in the leading national sires. By 2010, 59% were dominantly Kedaka, 21% Itozakura and 20% Tajima.

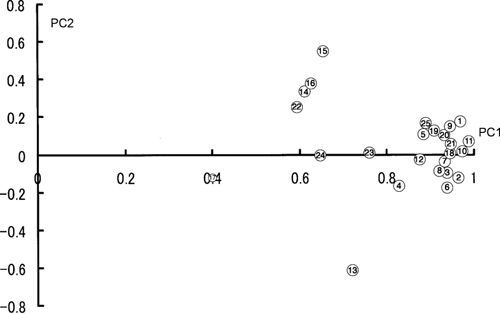

An incisive perspective on retained/loss of diversity across 25 prefecture herds was provided by Honda et al (above) in 2002 using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to help summarise multi-dimensional information, and Nei’s standard genetic differences. The sample was 25 prefectures with 2000 or more pedigree-recorded Black Wagyu cows alive and 10yo or less at August 2001.

The useful application of this knowledge for non-Japanese breeders may simply be the clear identification of the five Chugoku cradle prefecture bloodlines as ongoing, individual genetic resources with differentiated performance. The five to follow are: Hyogo, Tottori, Shimane, Okayama and Hiroshima (#17 – hiding under the 0.4 figure on the PC1 axis).

PCA Analysis. Genetic relationships between 25 prefectural sub-populations

(Click for larger picture).

Plots of the factor loadings of 25 subpopulations on PC1 and PC2 plane. 1, Hokkaido; 2, Aomori; 3, Iwate; 4, Miyagi; 5, Akita; 6, Yamagata; 7, Fukushima; 8, Ibaragi; 9, Tochigi; 10, Gunma; 11, Nagano; 12, Gifu; 13, Hyogo; 14, Tottori; 15, Shimane; 16, Okayama; 17, Hiroshima; 18, Yamaguchi; 19, Saga; 20, Nagasaki; 21, Kumamoto; 22, Ooita; 23, Miyazaki; 24, Kagoshima; 25, Okinawa. (Source: Honda, T., Nomura, T., Yamguchi, Y., & Mukai, F. 2002. ‘Pedigree analysis of a genetic subdivision in a population of Japanese Black cattle. Animal Science Jnl, 73, 445-452)

Hiroshima (17) shows the smallest factor loading for the PC1 axis. The authors explain that because this herd had relatively low relationships with all other sub-populations it seemed to have a unique genetic constitution. Considering the PC2 axis, Hyogo (13) had the lowest factor loading while Shimane, Tottori and Okayama showed the largest.

Taking into account other inbreeding and relationship coefficient data in the study that showed these three as having the lowest (most differentiated) relationships to Hyogo, the cluster arrangements of the PC2 factor were interpreted as mainly determined by relationship with Hyogo.

In addition to the five Chugoku ‘cradle’prefectures, the PCA chart separated three other genetic sub-populations from the conspicuous ‘Hyogo related’ cluster, namely the Kyushu district prefectures of Ooita, Myiazaki and Kagoshima (22,23,24). These are physically located a short geographic distance from Chugoku across the Kammon strait, still within Black Wagyu heartland.

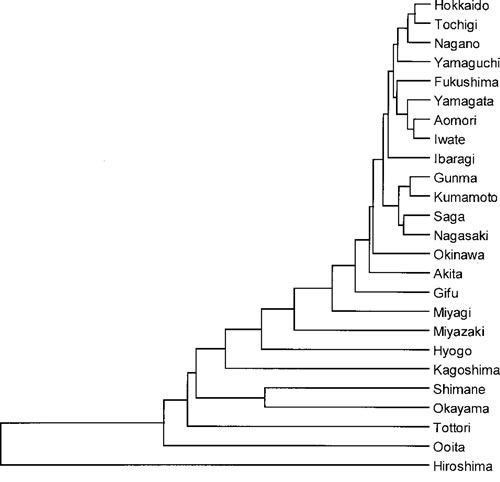

The authors employed further PC analysis to examine the relative positions of these three (unrecognised as contributors to genetics beyond Japan) to the 25 and then constructed the following dendrogram, which provides a complementary, graphical view of relationships between all 25 genetic subpopulations, with the graphic clearly contrasting 17 prefectures of commodity herd genetics (related most to Hyogo of the Chugoku group) with the more differentiated herds at base.

Source: Honda, T., Nomura, T., Yamguchi, Y., & Mukai, F. 2002. ‘Pedigree analysis of a genetic subdivision in a population of Japanese Black cattle. Animal Science Jnl, 73, 445-452

(Click for larger picture).

Fig. Dendrogram showing the genetic relationships among the 25 subpopulations based on Nei’s standard genetic distance.

The authors concluded that the Chugoku sub-populations, long a source of genetics for the entire national herd, have each maintained unique genetic compositions ‘at some level’. They called for maintenance of genetically different sub-populations to support breed improvement and emphasis on traits such as reproductive performance, maternal ability and growth rate.

An obvious danger lies in the scale of Black Wagyu production in the Chugoku district, compared with other regions in Japan. Chugoku herds today are relatively small. (See herd population data under Japanese Production Systems.)

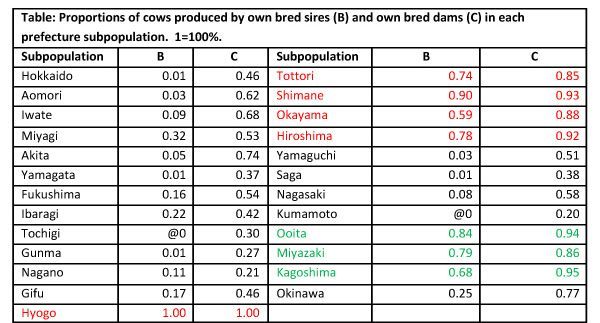

Before leaving the 2002 study, it is interesting to look at one further table. In considering ‘why ?’ eight sub-populations stood apart in PCA clusters, the scientists analysed prefectural herds to determine proportions of reproductive cows within each produced by own ‘prefecture bred sires’ (B) and own ‘prefecture bred cows’ (C).

Source: Honda, T., Nomura, T., Yamguchi, Y., & Mukai, F. 2002. ‘Pedigree analysis of a genetic subdivision in a population of Japanese Black cattle. Animal Science Jnl, 73, 445-452

(Click for larger picture).

The resulting table reveals that the five Chugoko (and three Kyushu) herds had much higher ‘own bred’ proportions – indicating maintained unique joining practices – and also maintaining the long Japanese ‘tsuru’ tradition.

The Tsuru Tradition Continues

The ‘tsuru’ tradition involves an emphasis on female selection and is a unique Japanese ‘take’ on in-breeding. Following is an edited version of a web-published explanation authored by Dr. Kiyoshi Namikawa, an Executive Director of ZENWA, the Japanese Wagyu association.

Tsuru is a popular name for inbred strains of native cattle. It describes a group of related cattle within a strain, representing superior and common external and productive traits for that strain based on genetic make-up. EG: One tsuru group originated from one excellent cow which produced 19 calves over 23 years. Two daughters inherited superior dam characteristics, and they formed two sub-strains. A son was backcrossed to his dam to fix desired traits. Two bulls were selected among offspring produced by son and mother mating. Cows of this strain were sired with one of the bulls reciprocally in the successive generations. Most female progeny were held nearby to enable observation of performance.

Dr Namikawa emphasises that tsuru strains were founded on maternal lines, “because reproductive and growing performance records were observed only for females in some closed place from their farm.” For the original text see Namikawa, pp 3-4.

In contrast, modern Japanese joining strategies in many non-traditional breeding areas are similar to contemporary Western assortative mating selection, frequently joining superior individuals from different sub-populations. A cursory glance over the pedigrees of the Top 10 Japanese sires for any recent year (see examples on this site), also reveals the modern popularity of this strategy at the national level. Notwithstanding, it is also certain that breeders would have looked first to the prefectural origins of all genetics, and as noted above, included this pedigree information in catalogue joining recommendations, such as “good for Fujiyoshi female”, etc.

Prefectural Bloodlines In US/Australia Original Imports

Finally, brief consideration might be given to the impact of post-1960s Japanese breeding fashions on the selection on the live export groups leaving Japan in the 1980s and 1990s – the founder cattle of modern American and Australian Wagyu herds. The fact that no comprehensive ‘coverage’ pattern is identifiable is almost certainly because most export breeders were selected to seed cross-breed enterprises rather than to found fullblood herds.

As a result, the export group genetic profile had an enormous, skew to Hyogo (Tajima) genetics, as would have been the case in normal Japanese crossbreeding selection. The highly significant exception was the Westholme herd now owned by AACo, which not only contained nearly half the number of breeding females exported in total, but also diverse bloodlines.

Nonetheless, even in the largely Tajima crush beyond Westholme, higher growth sires (mainly Itozakura/but all Chugoku strain) were included, largely to help maintain frame size in new generations of foreign-born fullblood sires for crossbred production and these larger-frame export sires can be readily traced to disparate Chugoku traditional lineages. So although genetic emphasis was heavily skewed, some diversity was captured for export and some of that remains today.

Let’s Talk About Your Wagyu Breeding Plan

We'll Find the Right Wagyu Breeding Solution for You

Call us: